Lesson 14 - Transistors and Digital Logic#

Lesson Objectives#

Objective |

Description |

|---|---|

14.1 |

Explain what a transistor is and describe its function. |

14.2 |

Identify the basic structure and operation of a transistor. |

14.3 |

Construct logic gates using transistors. |

14.4 |

Calculate the number of transistors required for a logic gate. |

14.5 |

Develop truth tables from logic diagrams. |

1. Introduction#

In earlier lessons, you analyzed circuits in series and parallel and computed voltages and currents for both direct current (DC) and alternating current (AC) systems.

In this lesson, we shift to digital applications of DC, where voltage levels represent binary states:

Logic 0 (LOW)

Logic 1 (HIGH)

Digital computation is enabled by controlling current flow such that circuit outputs settle to these discrete states. The fundamental device used to implement this controlled conduction is the transistor.

2. Transistor Fundamentals#

A transistor is a semiconductor device that can be used as:

an amplifier (analog operation), or

a switch (digital operation, emphasized in ECE 315).

Transistors are fabricated from doped semiconductor material, where controlled impurities modify electrical properties to form N-type and P-type regions.

Bipolar Junction Transistor (BJT)#

A Bipolar Junction Transistor (BJT) is a three-terminal semiconductor device that controls current flow using both electron and hole charge carriers, which is why it is referred to as bipolar. BJTs are formed by joining three doped semiconductor regions to create either an NPN or PNP structure.

Structure#

A BJT consists of three regions:

Emitter – Heavily doped to inject charge carriers

Base – Thin, lightly doped region that controls conduction

Collector – Moderately doped region that collects carriers

In an NPN transistor, the emitter and collector are N-type and the base is P-type.

In a PNP transistor, the emitter and collector are P-type and the base is N-type.

Fig. 1. NPN BJT structure showing N-type emitter and collector with a P-type base.

Fig. 2. PNP BJT structure showing P-type emitter and collector with an N-type base.

Operation#

The BJT is a current-controlled device. A small current applied to the base, \(I_B\), allows a much larger current to flow between the collector and emitter, \(I_C\).

A simplified relationship is:

where \(\beta\) is the current gain of the transistor.

In digital applications:

\(I_B = 0\) → transistor is OFF

\(I_B > 0\) → transistor is ON

Because base current controls collector current, BJTs are well suited for amplification and switching applications. However, they generally consume more power than field-effect transistors when scaled to large digital systems.

Field-Effect Transistor (FET)#

A Field-Effect Transistor (FET) is a three-terminal semiconductor device in which current flow is controlled by an electric field. Unlike BJTs, FETs are unipolar devices, meaning conduction is primarily due to one type of charge carrier (either electrons or holes).

Structure#

A FET consists of:

Source – Where charge carriers enter

Drain – Where charge carriers exit

Gate – Controls current flow through the channel

The most common FET used in digital systems is the MOSFET (Metal-Oxide-Semiconductor Field-Effect Transistor). Two primary types are used:

NMOS (N-channel MOSFET)

PMOS (P-channel MOSFET)

Modern integrated circuits use CMOS (Complementary MOS) technology, which combines NMOS and PMOS devices to reduce power consumption.

Operation#

The FET is a voltage-controlled device. Applying a voltage to the gate, \(V_{GS}\), creates an electric field that modulates the conductivity of the channel between source and drain.

\(V_{GS}\) is the voltage applied between the gate and source terminals.

\(V_{th}\) is the minimum voltage required to create a conductive channel between the drain and source.

For a MOSFET:

\(V_{GS} < V_{th}\) → transistor is OFF

\(V_{GS} \geq V_{th}\) → transistor is ON

Because the gate draws negligible steady-state current, MOSFETs consume significantly less power than BJTs. This makes them ideal for:

Microprocessors

Memory circuits

High-density integrated circuits

Modern CPUs contain billions of MOSFETs operating at high clock frequencies with very low power per device.

Comparison: BJT vs. FET#

Characteristic |

BJT |

FET |

|---|---|---|

Control Mechanism |

Current-controlled (\(I_B\)) |

Voltage-controlled (\(V_{GS}\)) |

Carrier Type |

Bipolar (electrons and holes) |

Unipolar (one carrier type) |

Input Current |

Requires base current |

Negligible gate current |

Power Efficiency |

Higher power consumption |

Lower power consumption |

Primary Modern Use |

Amplifiers, discrete circuits |

Integrated circuits, CPUs |

4. Semiconductor Carrier Model for Switching#

A semiconductor is neither a perfect conductor nor a perfect insulator. Its conductivity is controlled by doping:

N-type regions have excess electrons (majority carriers),

P-type regions have holes (majority carriers).

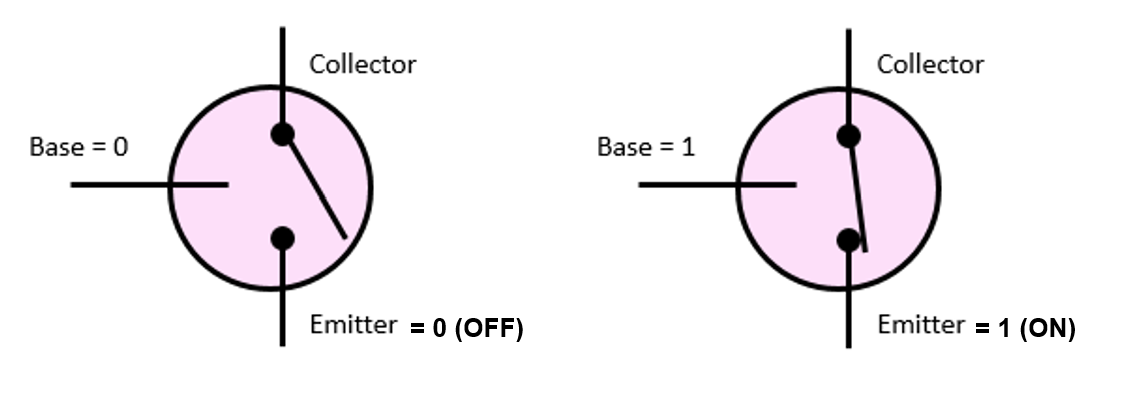

The switching concept can be introduced using an NPN device model.

Fig. 3. Conceptual carrier model illustrating how base drive enables conduction between collector and emitter.

Base drive (a small current into the base) modifies the effective barrier in the base region, enabling a much larger collector-to-emitter current. In digital design, we leverage this behavior to implement controlled ON/OFF conduction states.

5. Transistor as an Ideal Switch#

Rather than tracking individual carriers, digital logic typically uses a simplified abstraction: the transistor behaves like an electrically controlled switch.

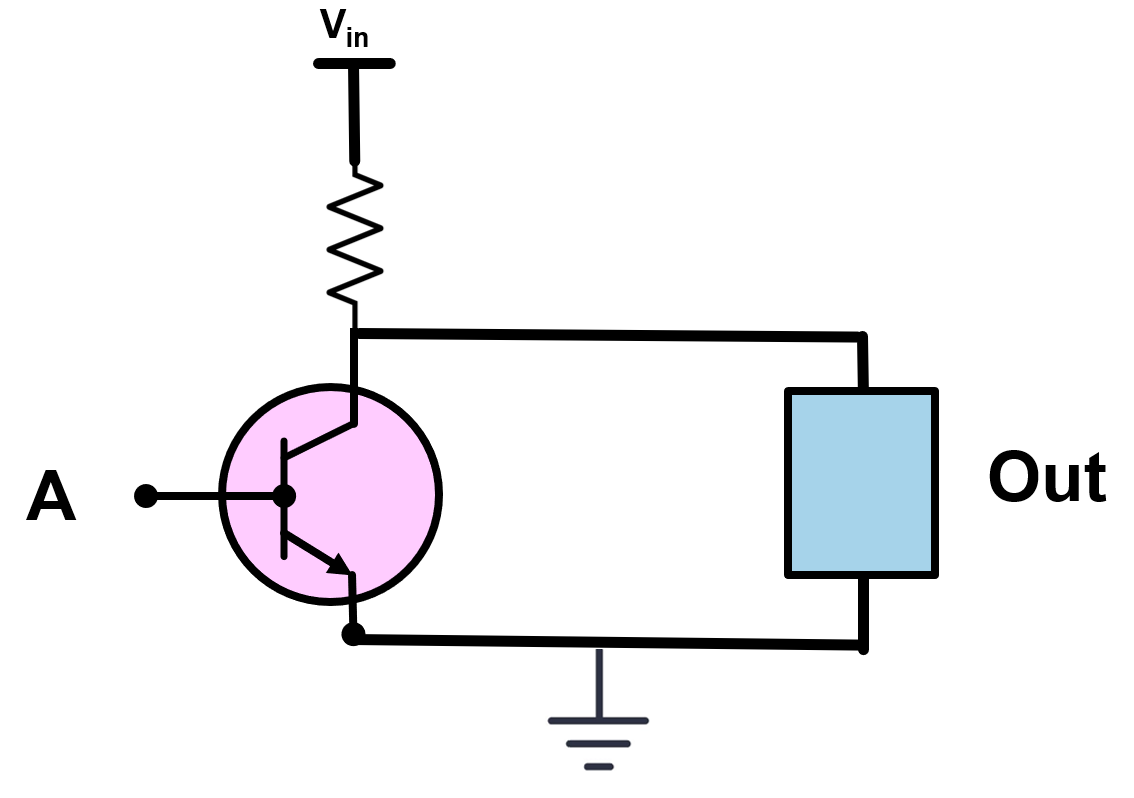

Fig. 4. Idealized switch model of a transistor controlled by the base input.

For a first-order model in ECE 315, we treat the transistor as producing an output consistent with the input control:

Base input |

Output |

|---|---|

0 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

This abstraction allows transistor networks to be analyzed using series/parallel reasoning and truth tables.

6. Truth Tables#

A truth table enumerates all possible combinations of binary inputs and lists the corresponding output.

For \(n\) independent inputs, there are \(2^n\) input combinations.

Truth tables provide a complete input/output specification for a logic function and are the standard tool for analyzing digital circuits.

7. Logic Gates Using Transistor Switch Networks#

By combining transistor switches in series and parallel, we implement fundamental logic operations.

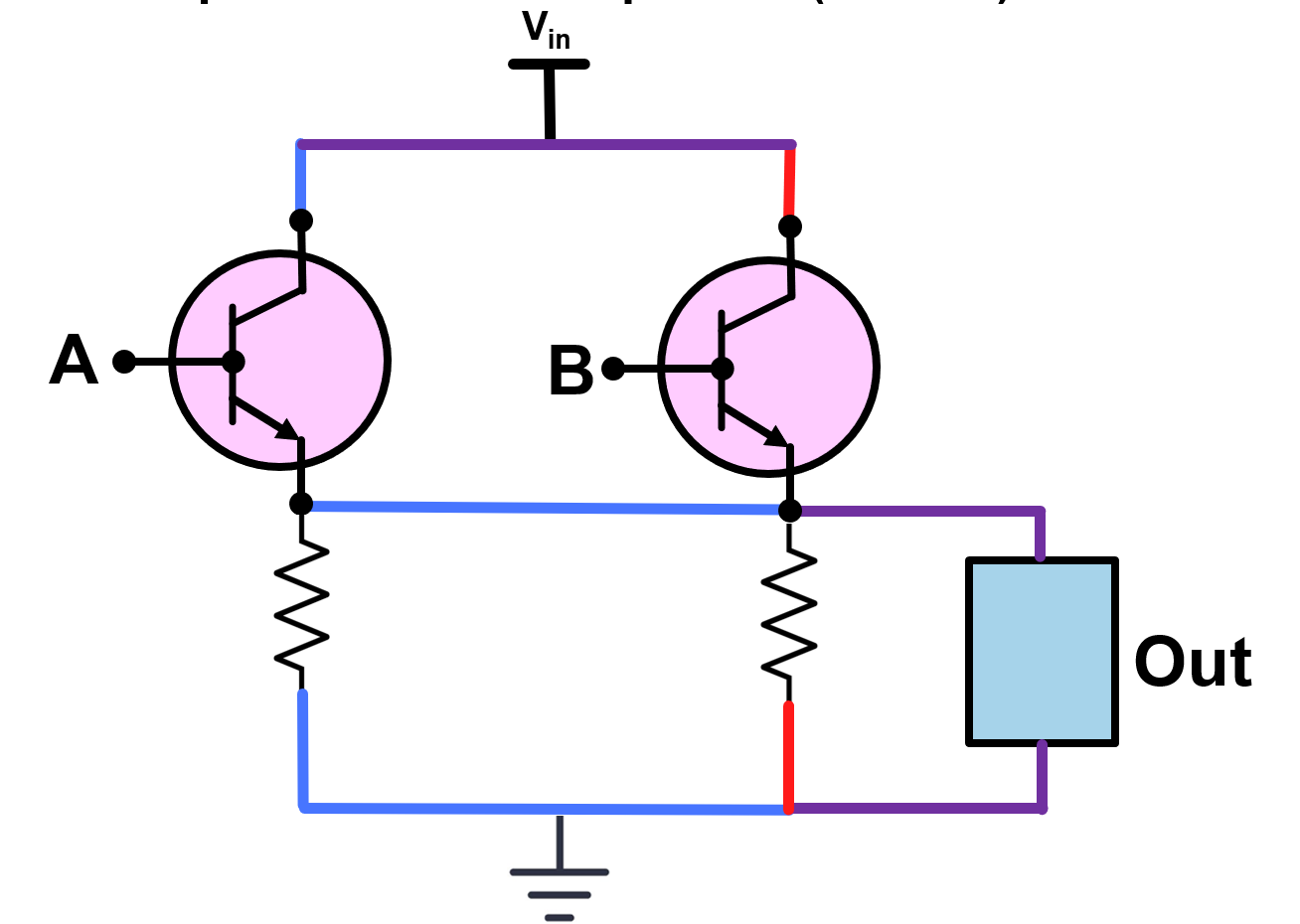

7.1 AND Gate (Series Configuration)#

Two transistor switches in series implement the AND function because the current path conducts only if both switches are closed.

Fig. 5. Two-switch series network implementing an AND function.

The truth table below describes the behavior of a two-input AND gate.

\(A\) |

\(B\) |

Out |

|---|---|---|

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

There are \(2^2 = 4\) possible input combinations for two independent binary variables, \(A\) and \(B\). The output is equal to 1 only when both inputs are 1. In all other cases, the output is 0.

From a transistor-switch perspective, this behavior results from placing two switches in series. Current can flow to the output only if:

Switch \(A\) is closed (\(A = 1\)), and

Switch \(B\) is closed (\(B = 1\))

If either switch is open (\(0\)), the conduction path is broken and the output remains low. This directly illustrates the logical definition of the AND operation:

Thus, the truth table formally captures the physical behavior of two controlled conduction paths arranged in series.

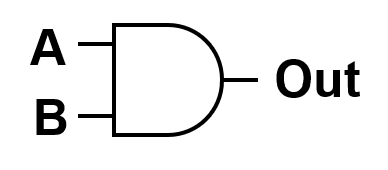

Symbol:

The schematic symbol for an AND gate consists of a flat vertical line on the left (input side) and a curved semicircular shape on the right (output side). Two or more input lines enter from the left, and a single output line exits on the right.

The flat left edge represents the requirement that all inputs must be present, while the rounded right edge reflects the combined logical output. In Boolean notation, the AND operation is represented as:

When analyzing schematics, any symbol with a flat left side and curved right side (without an inversion bubble) represents an AND function.

Fig. 6. AND-gate schematic symbol.

7.2 OR Gate (Parallel Configuration)#

Two transistor switches in parallel implement the OR function because a conductive path exists if either switch is closed.

Fig. 7. Two-switch parallel network implementing an OR function.

Truth table:

The truth table below describes the behavior of a two-input OR gate.

\(A\) |

\(B\) |

Out |

|---|---|---|

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

For two independent binary inputs, there are \(2^2 = 4\) possible input combinations. The output is equal to 1 whenever at least one input is 1. The only time the output is 0 is when both inputs are 0.

From a transistor-switch perspective, this behavior results from placing two switches in parallel. Current can reach the output if:

Switch \(A\) is closed (\(A = 1\)), or

Switch \(B\) is closed (\(B = 1\))

If both switches are open (\(A = 0\) and \(B = 0\)), there is no complete conduction path and the output remains low.

This matches the Boolean definition of the OR operation:

Thus, the truth table formally represents the physical behavior of two controlled conduction paths arranged in parallel.

Symbol:

The schematic symbol for an OR gate has a curved input side and a pointed curved output side. Two or more input lines enter from the left, and a single output line exits on the right.

Unlike the AND gate, which has a flat left edge, the OR gate’s left side is concave, indicating that any one of the inputs can produce an output. The pointed right side represents the logical combination of the inputs.

In Boolean notation, the OR operation is written as:

When interpreting circuit diagrams, any symbol with a fully curved input side and pointed output (without an inversion bubble) represents an OR function.

Fig. 8. OR-gate schematic symbol.

7.3 NOT Gate (Inverter)#

The NOT operation inverts the input. In switch terms, the output is high when the controlled conduction path is open (and low when closed), depending on where the output node is measured in the circuit.

Fig. 9. Inverter (NOT) concept circuit using a transistor switch abstraction.

Truth table:

The truth table below describes the behavior of a NOT gate (inverter).

\(A\) |

Out |

|---|---|

0 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

A NOT gate has a single input, so there are \(2^1 = 2\) possible input combinations. The output is always the logical inverse of the input.

If \(A = 0\), then \(\text{Out} = 1\)

If \(A = 1\), then \(\text{Out} = 0\)

This operation is called inversion or complementation and is written in Boolean form as:

From a switching perspective, the NOT gate reverses the relationship between input and output. Instead of the output matching the input (as in a simple switch), the output reflects the opposite logic state. This inversion is fundamental in digital design because it allows signals to be complemented and enables the construction of more complex logical functions.

Symbol:

The schematic symbol for a NOT gate consists of a triangle pointing to the right with a small circle, called an inversion bubble, at the output.

The triangle represents signal flow from input to output.

The small circle indicates logical inversion.

The presence of the bubble is critical — it signifies that the output is the complement of the input.

In Boolean notation, the NOT operation is written as:

When analyzing schematics, any logic symbol with a small circle at its output represents an inverted signal. If that bubble appears on the output of an AND or OR gate, it indicates NAND or NOR behavior, respectively.

Fig. 10. NOT-gate (inverter) schematic symbol.

8. Transistor Count and Scaling#

Complex computation emerges from repeated use of simple logic gates. Gate complexity is often estimated using transistor count.

Device |

Transistors |

|---|---|

NOT gate |

1 |

2-input AND gate |

2 |

2-input OR gate |

2 |

6502 CPU (early Apple computer) |

4,528 |

Apollo 11 CPU |

17,000 |

1st Gen F-16 CPU |

110,000 |

PlayStation 2 |

53,500,000 |

First iPhone CPU |

125,000,000 |

iPhone 16 CPU |

19,000,000,000 |

Intel i9-13900K CPU |

26,000,000,000 |

As transistor count increases, systems can implement more parallel logic and higher functional density. Modern processors achieve their capability by coordinating extremely large numbers of transistor switches at high clock rates.

Transistor Count Example#

How many transistors?#

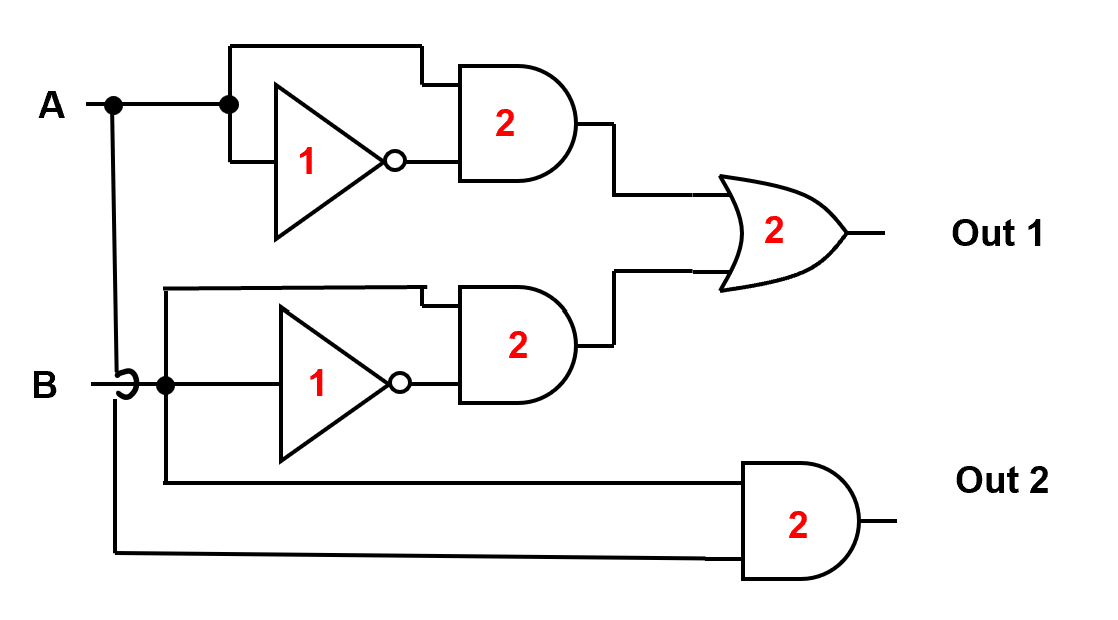

The circuit shown implements the addition of two single-bit inputs, \(A\) and \(B\).

This structure corresponds to a half-adder, producing:

Out 1 → Sum

Out 2 → Carry

To determine the total number of transistors required, we count the devices used in each gate.

From the diagram:

From the diagram:

Each NOT gate uses 1 transistor

Each 2-input AND gate uses 2 transistors

The 2-input OR gate uses 2 transistors

Gate Count Breakdown#

There are:

2 NOT gates → \(1 \times 2 = 2\)

3 AND gates → \(2 \times 3 = 6\)

1 OR gate → \(2 \times 1 = 2\)

Total transistor count:

Thus, this circuit requires 10 transistors to implement the addition of two binary inputs.

Logic Diagram: Determine the Output#

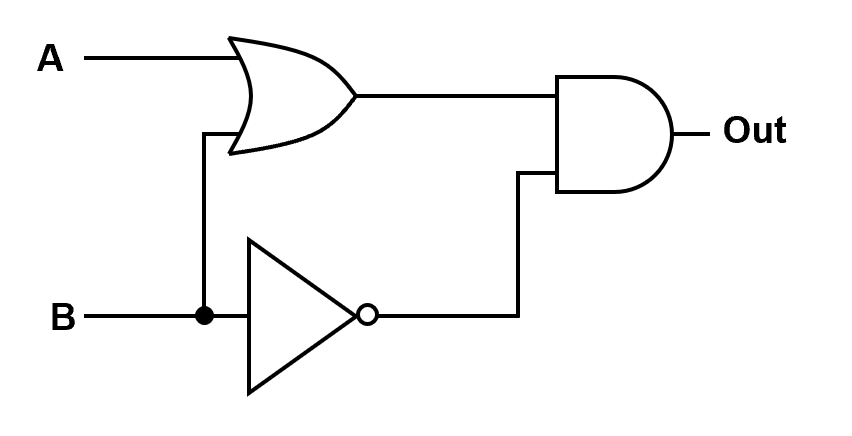

Given the logic diagram below, determine the output Out for all input combinations of \(A\) and \(B\).

For each input pair \((A, B)\), follow the signal flow through the circuit:

OR gate input: \(A\) and \(B\) → produces the OR output

NOT gate input: \(B\) → produces \(\text{NOT}(B)\)

AND gate input: OR output and NOT output → produces Out

Row 1: \(A = 0\), \(B = 0\)#

OR gate: \(0\) OR \(0\) → \(0\)

NOT gate: NOT\((0)\) → \(1\)

AND gate: \(0\) AND \(1\) → \(0\)

Out = 0

Row 2: \(A = 0\), \(B = 1\)#

OR gate: \(0\) OR \(1\) → \(1\)

NOT gate: NOT\((1)\) → \(0\)

AND gate: \(1\) AND \(0\) → \(0\)

Out = 0

Row 3: \(A = 1\), \(B = 0\)#

OR gate: \(1\) OR \(0\) → \(1\)

NOT gate: NOT\((0)\) → \(1\)

AND gate: \(1\) AND \(1\) → \(1\)

Out = 1

Row 4: \(A = 1\), \(B = 1\)#

OR gate: \(1\) OR \(1\) → \(1\)

NOT gate: NOT\((1)\) → \(0\)

AND gate: \(1\) AND \(0\) → \(0\)

Out = 0

Final Truth Table#

\(A\) |

\(B\) |

Out |

|---|---|---|

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

Key Insights#

Notice that the output is 1 only when \(A = 1\) and \(B = 0\).

From the signal flow:

The OR gate ensures the first input to the AND gate is 1 whenever either \(A\) or \(B\) is 1.

The NOT gate forces the second input to the AND gate to be 1 only when \(B = 0\).

So for the AND gate to output 1:

The OR output must be 1 → this requires \(A = 1\) or \(B = 1\).

The NOT output must be 1 → this requires \(B = 0\).

The only way both conditions are satisfied simultaneously is when:

\(A = 1\)

\(B = 0\)

Therefore, the circuit effectively behaves like:

A is true while B is false.

Logic Diagram Output Analysis#

Below is the given logic circuit:

This circuit first sends inputs \(A\) and \(B\) into an AND gate.

The output of that AND gate then feeds into an OR gate.

Input \(B\) is also routed directly into the OR gate.

Step 1: Understand the Structure#

The circuit implements:

AND stage: combines \(A\) and \(B\)

OR stage: combines the AND output with \(B\)

Visually labeled:

Step 2: Evaluate Row-by-Row#

We now trace each input combination through the circuit.

Row 1: \(A = 0\), \(B = 0\)#

AND gate: \(0\) AND \(0\) → \(0\)

OR gate: \(0\) OR \(0\) → \(0\)

Out = 0

Row 2: \(A = 0\), \(B = 1\)#

AND gate: \(0\) AND \(1\) → \(0\)

OR gate: \(0\) OR \(1\) → \(1\)

Out = 1

Row 3: \(A = 1\), \(B = 0\)#

AND gate: \(1\) AND \(0\) → \(0\)

OR gate: \(0\) OR \(0\) → \(0\)

Out = 0

Row 4: \(A = 1\), \(B = 1\)#

AND gate: \(1\) AND \(1\) → \(1\)

OR gate: \(1\) OR \(1\) → \(1\)

Out = 1

Completed Truth Table#

\(A\) |

\(B\) |

Out |

|---|---|---|

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

Key Insight#

Because input \(B\) feeds directly into the OR gate, whenever \(B = 1\), the output must be 1, regardless of \(A\).

When \(B = 0\), the AND gate cannot produce a 1 (since \(A \cdot 0 = 0\)), so the output must be 0.

Therefore, even though multiple gates are present, the overall circuit simplifies to:

This is an excellent example of how a seemingly complex logic diagram can reduce to a much simpler function.

Multi-Input Logic Gates#

AND and OR gates are not limited to two inputs. They can be constructed with three or more inputs, and the same logical rules apply — just extended across all inputs.

For a logic gate with \(n\) independent inputs, the number of possible input combinations is:

Each additional input doubles the number of possible combinations.

Example: 3-Input AND Gate#

For three inputs \(A\), \(B\), and \(C\):

Total combinations: $\( \)2^3 = 8\( \)$

Truth table:

\(A\) |

\(B\) |

\(C\) |

Out |

|---|---|---|---|

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

Key Rule:

A multi-input AND gate outputs 1 only if all inputs are 1.

If any input is 0, the output is 0.

Example: 3-Input OR Gate#

Truth table:

\(A\) |

\(B\) |

\(C\) |

Out |

|---|---|---|---|

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

Key Rule:

A multi-input OR gate outputs 1 if at least one input is 1.

The only time the output is 0 is when all inputs are 0.

Important Takeaway#

Two inputs → \(2^2 = 4\) combinations

Three inputs → \(2^3 = 8\) combinations

Four inputs → \(2^4 = 16\) combinations

Each additional input doubles the size of the truth table.

This exponential growth becomes important when designing larger digital systems, as the number of input combinations increases rapidly with each added variable.

Logic Diagram Output Analysis (3 Inputs)#

Given the logic diagram below, determine the output Out for all input combinations of \(A\), \(B\), and \(C\).

Step-by-Step Process#

This circuit has two stages:

OR stage: Inputs \(A\) and \(B\) enter an OR gate.

AND stage: The OR output is then ANDed with inputs \(B\) and \(C\) using a 3-input AND gate.

So, for each row:

Compute the OR output from \(A\) and \(B\)

Then evaluate the 3-input AND gate using:

(OR output), \(B\), and \(C\)

Completed Truth Table#

\(A\) |

\(B\) |

\(C\) |

Out |

|---|---|---|---|

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

Key Insights#

The output depends on both \(B\) and \(C\).

Notice that Out = 1 only in the rows where both \(B = 1\) and \(C = 1\).Input \(A\) does not affect the final outcome.

Compare the two rows where \(B = 1\) and \(C = 1\):\(A = 0\), \(B = 1\), \(C = 1\) → Out = 1

\(A = 1\), \(B = 1\), \(C = 1\) → Out = 1

Changing \(A\) does not change the output.

Therefore, \(A\) is not influencing the final result.Pattern recognition shortcut:

When two rows differ only in one variable and produce the same output, that variable is not part of the final logic condition.Functional interpretation:

The output is 1 only when:\(B = 1\)

\(C = 1\)

In all other combinations, at least one of those inputs is 0, forcing the output to 0.

Conceptual takeaway:

Even though three inputs are present, the circuit effectively behaves like a 2-input AND gate using only \(B\) and \(C\).

This truth table represents a function where the output is true only when both \(B\) and \(C\) are true, regardless of the value of \(A\).

9. Summary#

In Lesson 14 you learned how transistor switching behavior enables digital logic and how that behavior scales to increasingly complex systems:

BJTs are formed from N-type and P-type regions (NPN and PNP structures).

Base drive enables controlled conduction between collector and emitter.

A simplified ideal-switch model allows transistors to be analyzed as digital ON/OFF devices.

Series switch networks implement AND behavior.

Parallel switch networks implement OR behavior.

Inversion (NOT) is achieved using a transistor-based inverter with an output bubble indicating logical complement.

Truth tables systematically enumerate all possible input combinations, where a circuit with \(n\) inputs has \(2^n\) possible states.

Multi-input logic gates extend the same AND/OR principles to three or more variables, doubling the number of combinations with each added input.

Complex logic diagrams can often be simplified by tracing signals stage-by-stage and recognizing dominant paths (e.g., direct OR inputs forcing output states).

Transistor count provides a quantitative measure of circuit complexity, and scaling transistor density enables modern computing systems.

Together, these concepts form the foundation for analyzing, designing, and simplifying digital logic circuits in ECE 315.